The company’s stance and that of its leading family members toward National Socialism were marked by initial restraint, pragmatic adaptation, and cooperation.

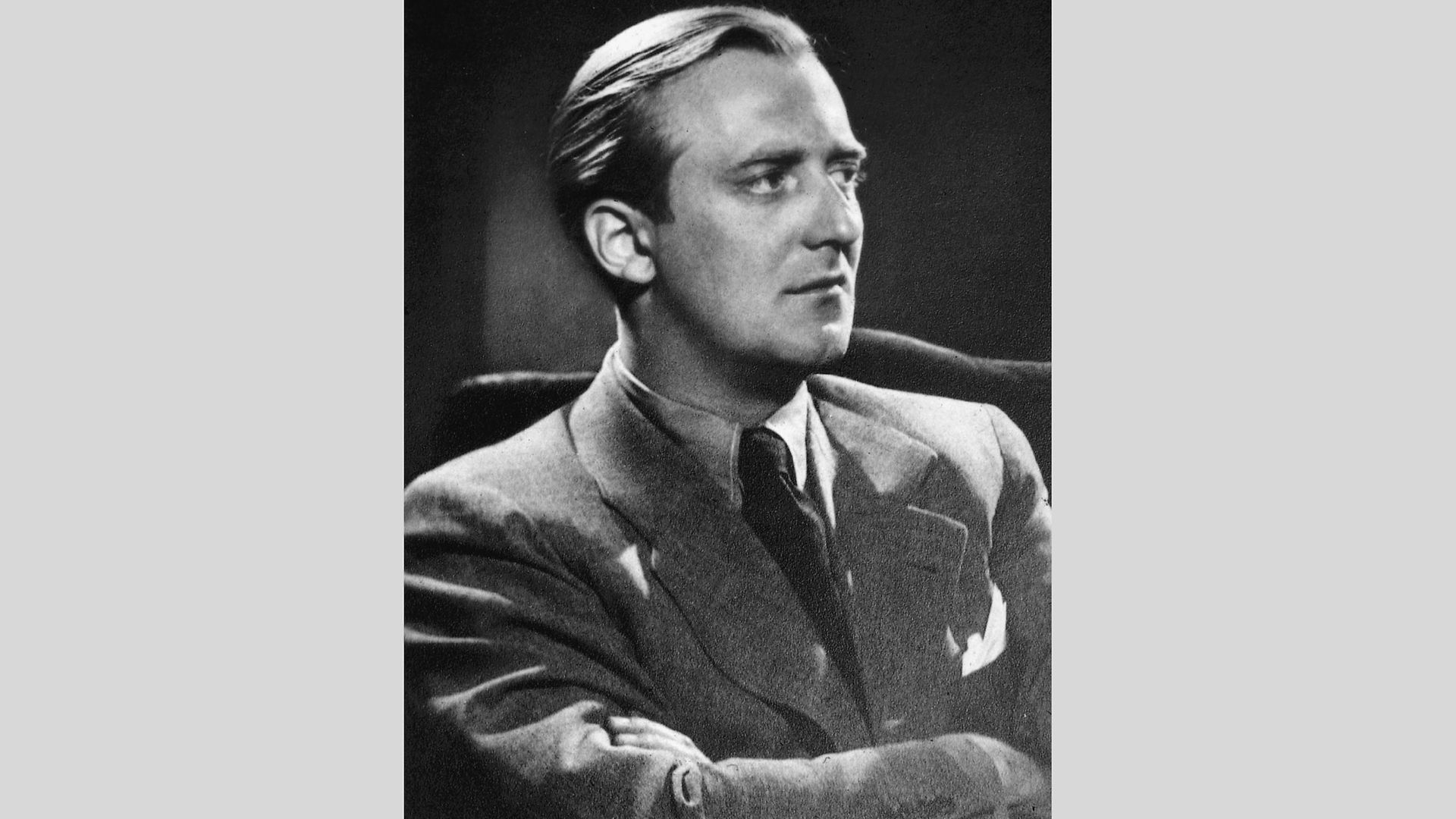

Hugo Henkel, originally liberal and politically active in the German Democratic Party (DDP), took over sole company leadership in 1930. His entrepreneurial focus was strongly oriented towards technology, efficiency, and building international markets. Although he viewed the Nazi seizure of power in 1933 with skepticism, he joined the NSDAP that same year – according to later statements, to protect the company. Eyewitnesses confirmed his efforts to avoid political interference.

The Henkel Pavilion at the Reich Exhibition “Schaffendes Volk” (“Working Nation”) on a postcard (1937)

Nevertheless, Hugo Henkel quickly adapted to the regime, was active in Nazi-affiliated committees until 1942, and publicly praised Hitler. The company participated in propaganda campaigns. In 1938, Hugo Henkel was ousted from company leadership by his nephew Werner Lüps (1906–1942) following a tax affair.

Overall, however, political statements from company management and family members remained the exception during these years. There is no clear ideological line within the family; rather, pragmatic opportunism prevailed, something that was widespread in business circles at the time.

The Political Attitudes of the Henkel Workforce

The political views of Henkel’s workforce during the Nazi era were far from uniform and reflected the societal tensions and upheavals of the time.

Company assembly for the inauguration of the monument in honor of company founder Fritz Henkel (1938)

Meeting of the Henkel Works Council in 1936

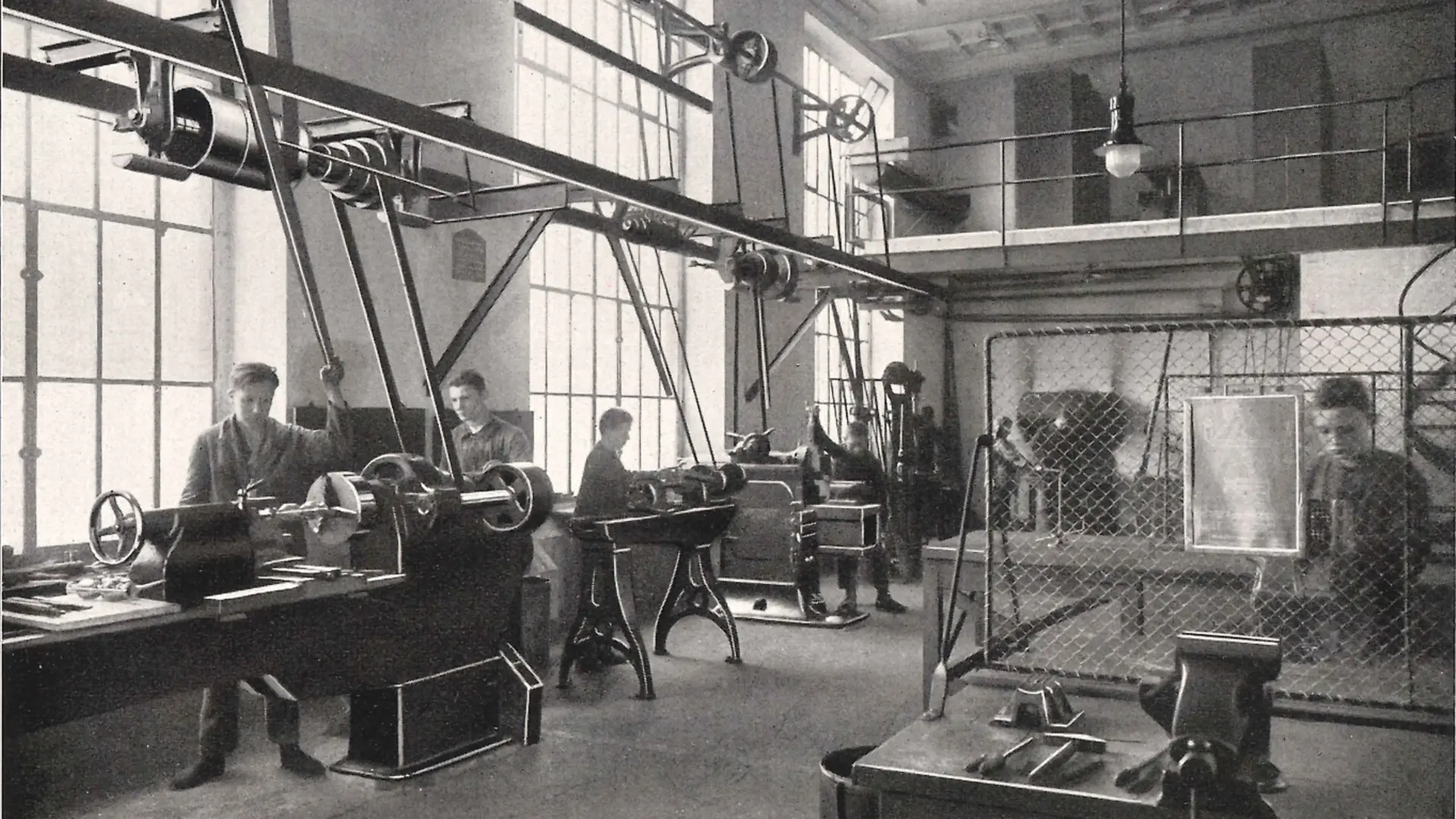

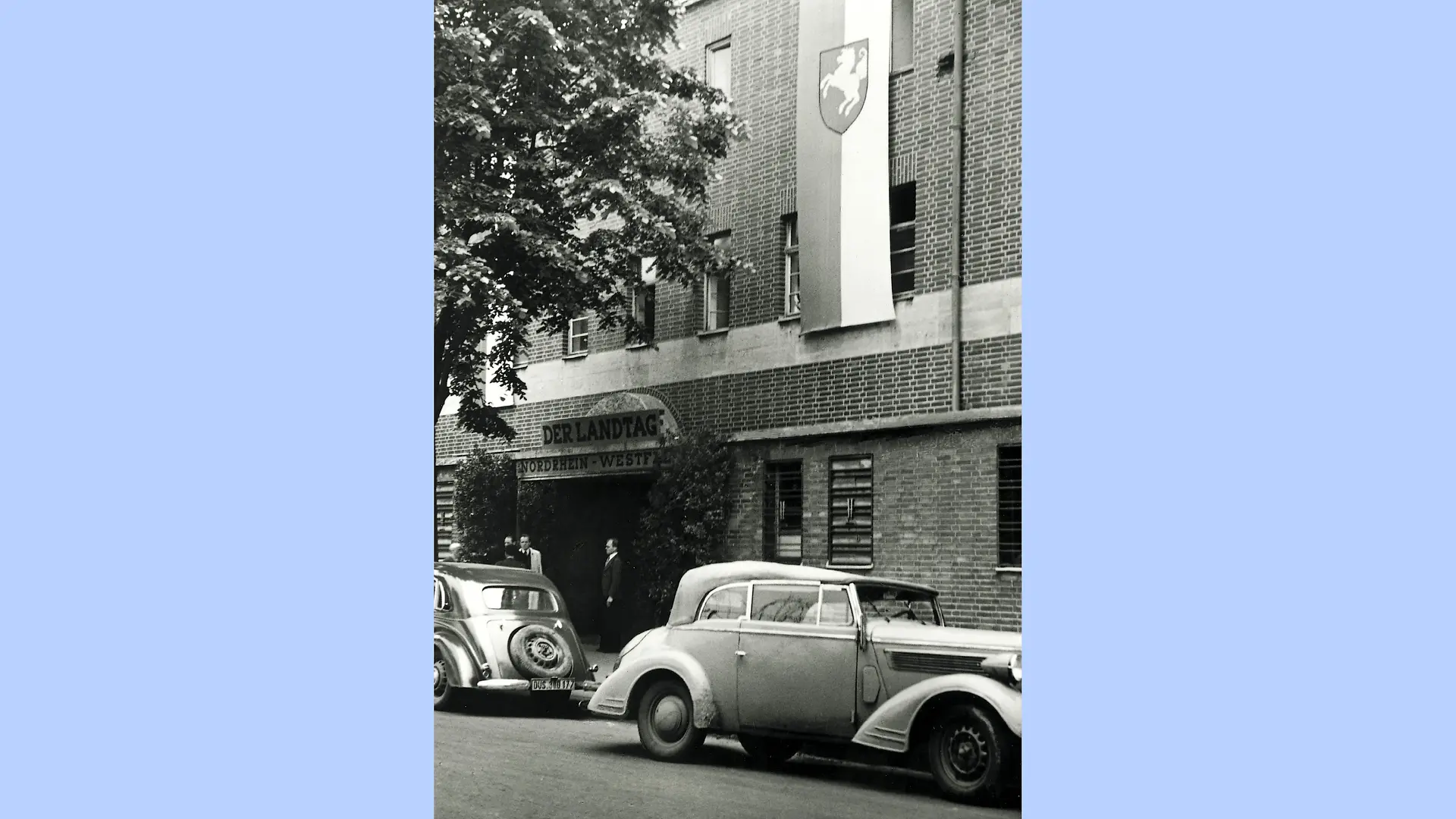

While the working class voted predominantly Social Democratic in the 1933 works council elections (66.5 percent), the white-collar employees showed a much stronger affinity for the NSDAP, which won four out of five seats in that group. According to Viktor Kirberg, then chairman of the works council, the proportion of NSDAP supporters among white-collar staff later rose to around 90 percent.

Membership of the NSDAP was particularly strong among executives such as managing directors, engineers, and department heads. Party membership increasingly became a prerequisite for career advancement.

Despite a clear electoral success for the Social Democrats, the works council was forced into line with the regime as early as May 1933. Kirberg lost his position but continued to be employed by the company as a foreman. The new “Council of Trust” was no longer freely elected but appointed by management and the Nazi Factory Cell Organization (NSBO). The sham elections of 1934 and 1935 met with little approval and were abolished entirely in 1936.

The attitude of the workforce remained ambivalent: many took part in Nazi events because attendance was expected, while others were more convinced supporters of the ideology – especially in the company’s upper ranks.

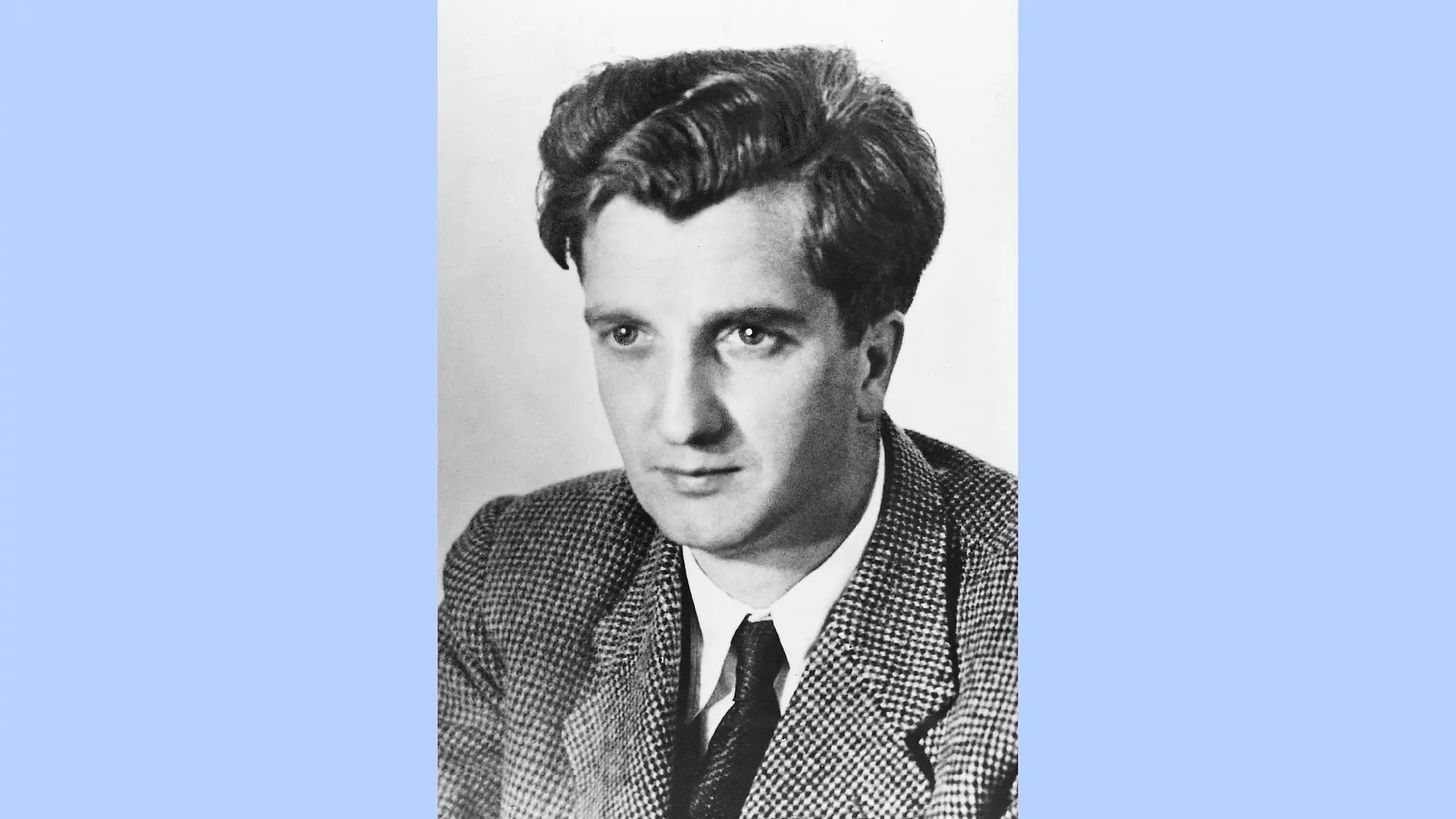

Henkel Under the Leadership of Werner Lüps

In 1938, Werner Lüps became the central figure in the company. The grandson of the company founder joined the NSDAP early and cultivated close ties with leading party members, which he strategically used to establish himself within the company.

His rise culminated in a plot against his uncle Hugo Henkel, who had been weakened by a tax affair after 1936. Lüps gathered incriminating material against Hugo Henkel. With the support of the National Socialists, Hugo Henkel was forced to resign as head of the company in the summer of 1938; he had to move to the supervisory board and no longer had any active influence on the development of the company.

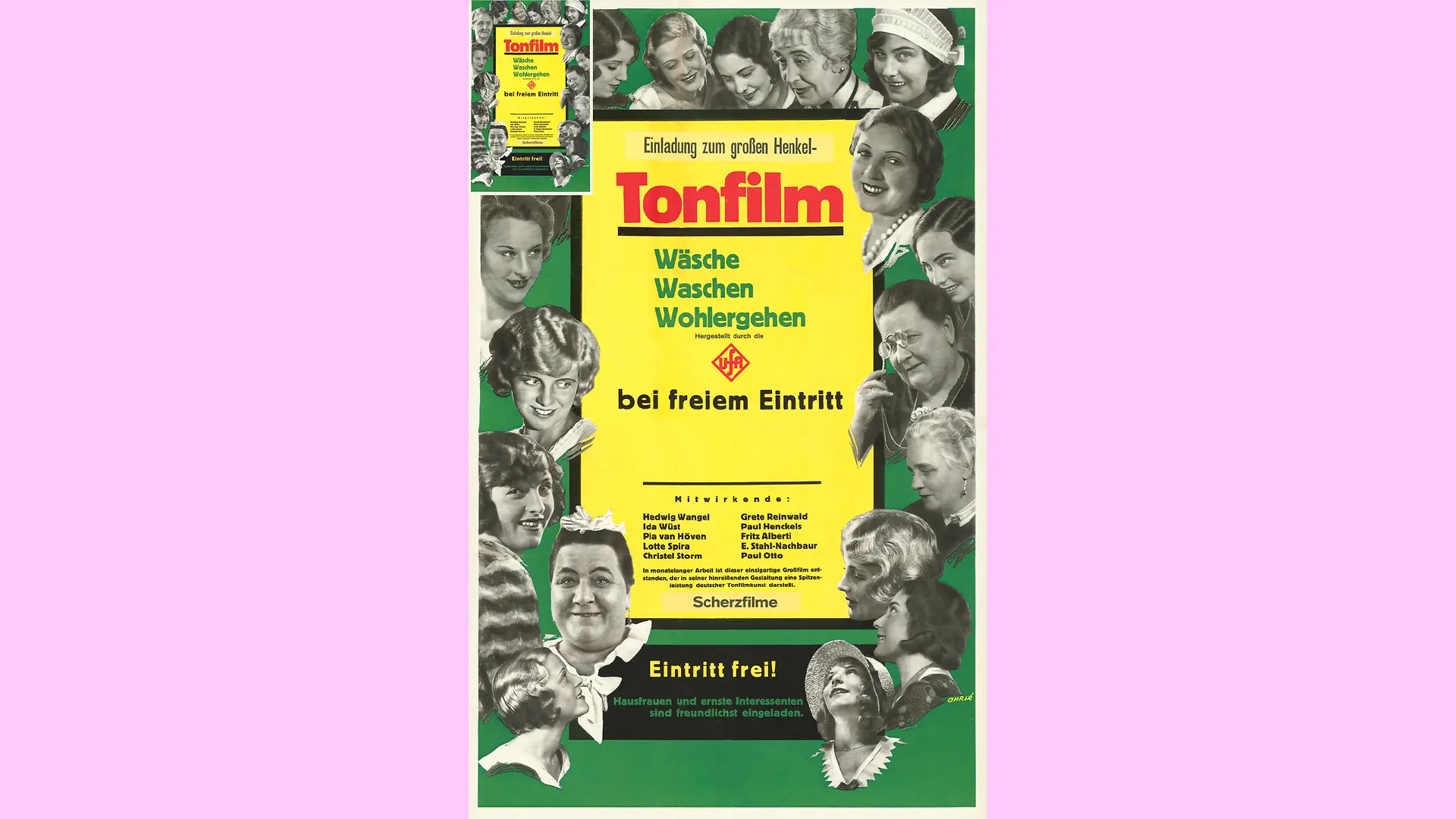

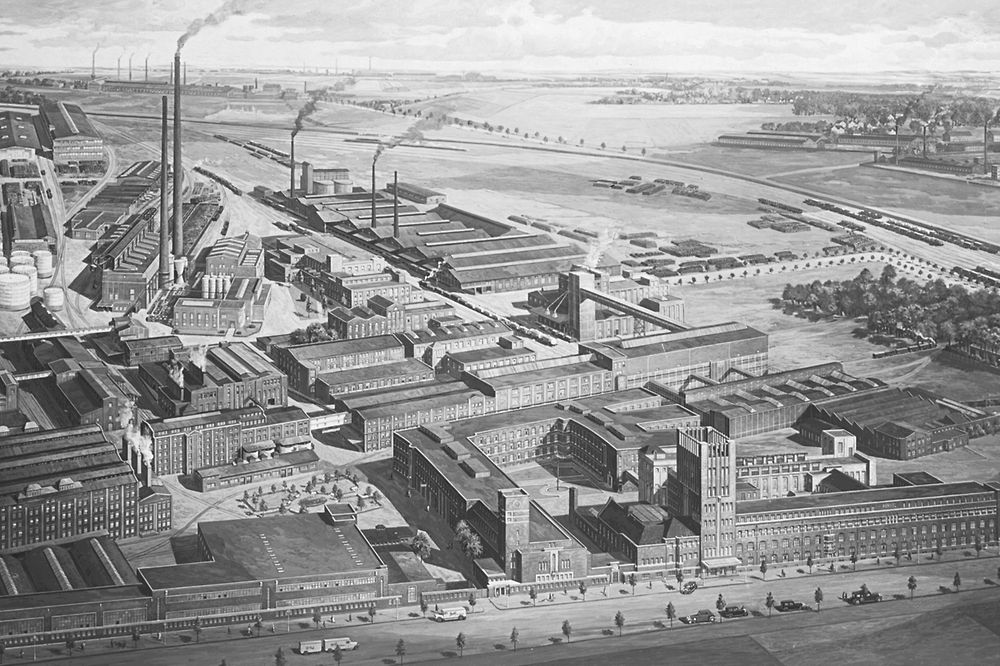

Lüps took over company leadership and steered Henkel onto a Nazi course. In 1940, the company was recognized as a “National Socialist Model Enterprise.” Lüps presented himself as a model economic leader and organized large-scale propaganda events at the company. He pursued ambitious entrepreneurial goals, including the takeover of Degussa, in order to expand Henkel into a second major chemical company alongside IG Farben. However, his aggressive strategy and management style met with increasing resistance – both within the company and within the Henkel family.

In 1942, the internal conflict escalated: Lüps once again made accusations against Hugo Henkel, but was himself removed from power by the majority of shareholders. Shortly afterwards, he died in a car accident. After his death, Dr. Jost Henkel (1909–1961), Hugo Henkel’s eldest son, became “plant manager.” Dr. Hermann Richter (1903–1982) took over as chairman of the management board. After 1945, the company distanced itself from Lüps and portrayed him as the sole “black sheep” – a simplistic view that ignored broader responsibility.

“Aryanizations” at Henkel During National Socialism

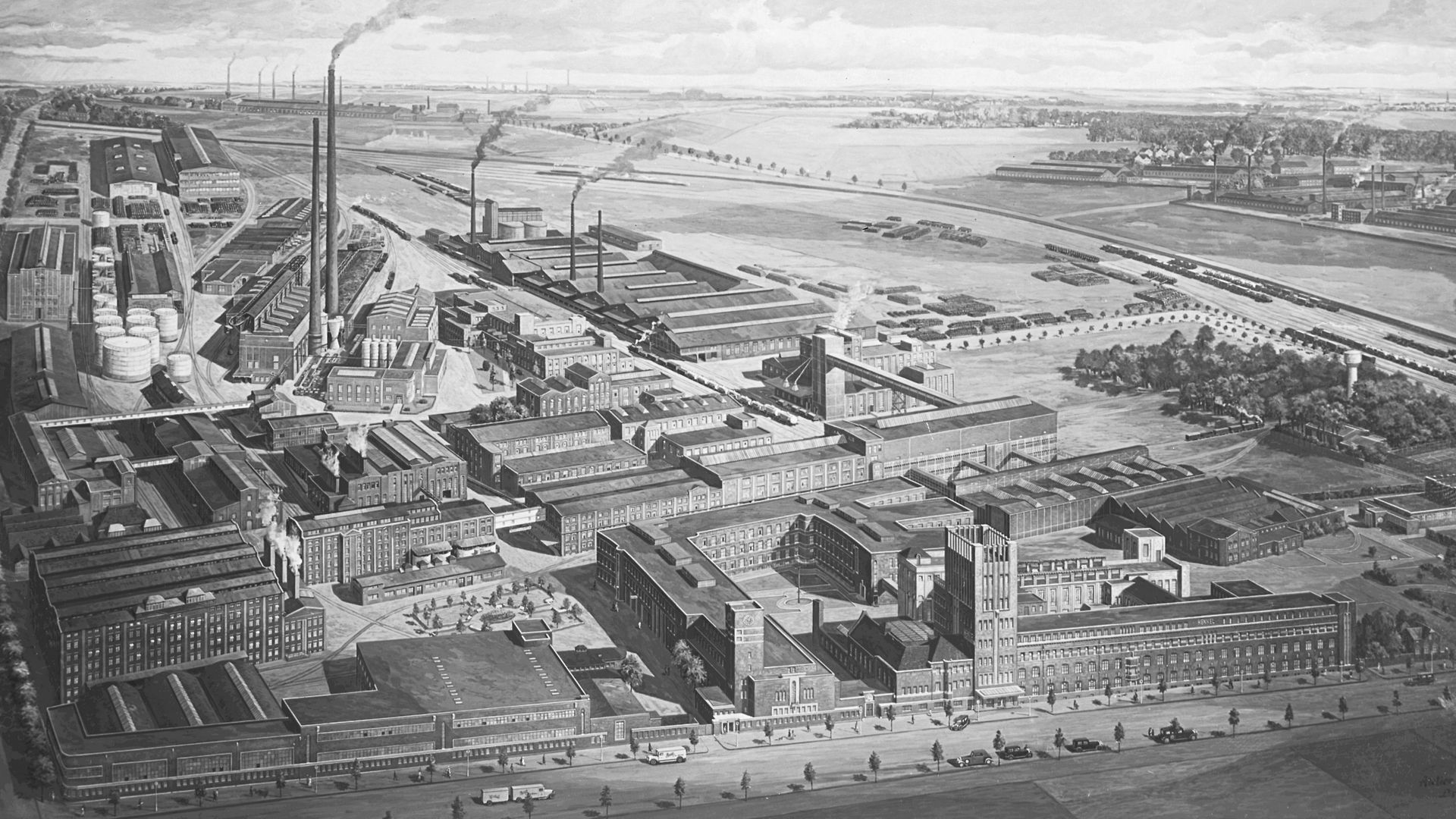

During the Nazi era, Henkel participated in several “Aryanizations” in order to gain economic advantages. The goals were to gain access to raw materials, expand production capacities, and secure market shares. Henkel usually acted indirectly through subsidiaries such as Dreiring or Dehydag. Among others, companies in Frankfurt an der Oder, Vienna, Prague, and Danzig were affected.

After 1945, Henkel attempted to relativize its role in the “Aryanizations,” but had to pay compensation in several cases. Individual acts of assistance for Jewish citizens, such as the rescue of the mother of a school friend of Konrad Henkel, do not alter the company’s complicity.

Forced Labor at Henkel During National Socialism

During World War II, Henkel, like most German companies, employed foreign forced laborers to compensate for labor shortages caused by conscription into the Wehrmacht. These included both civilian forced laborers and prisoners of war, brought to Germany via labor offices, military agencies, or forced recruitment. Workers came from countries including France, Belgium, Italy, Poland, and the Soviet Union.

Recreation room for French prisoners of war (1940)

Russian forced laborers in the Ata packaging plant (1943)

At the Düsseldorf-Holthausen site, the proportion of forced laborers peaked at 15.8 percent on December 31, 1943. At other sites, it exceeded 50 percent at times. Civilian forced laborers were housed in company-owned camps, while prisoners of war were held in facilities run by the Wehrmacht.

Living and working conditions varied greatly. While international conventions were mostly followed in the case of Western prisoners of war, Soviet prisoners of war and so-called “Eastern workers” suffered under particularly poor conditions. They were usually housed in barracks camps, separated according to nationality. Working hours ranged from 47 to 60 hours per week.

Henkel employed forced laborers in almost all areas and kept them under strict control. Contact with Germans was forbidden and severely punished. Three Soviet prisoners of war died at Henkel in Düsseldorf-Holthausen – two from poisoning after allegedly accidentally ingesting chemicals, and one who was shot by Wehrmacht guards after attempting to escape. After the war, many, especially “Eastern workers,” initially remained in the camps and were considered “displaced persons.”

Together with other German companies, Henkel joined the foundation initiative “Remembrance, Responsibility and Future” in 2000. The history of forced laborers and prisoners of war at Henkel was comprehensively researched on behalf of the company at the end of the 1990s before being published in the Henkel history book “Menschen und Marken” (People and Brands) in 2001.

Henkel, the Fat Gap, and Whaling During National Socialism

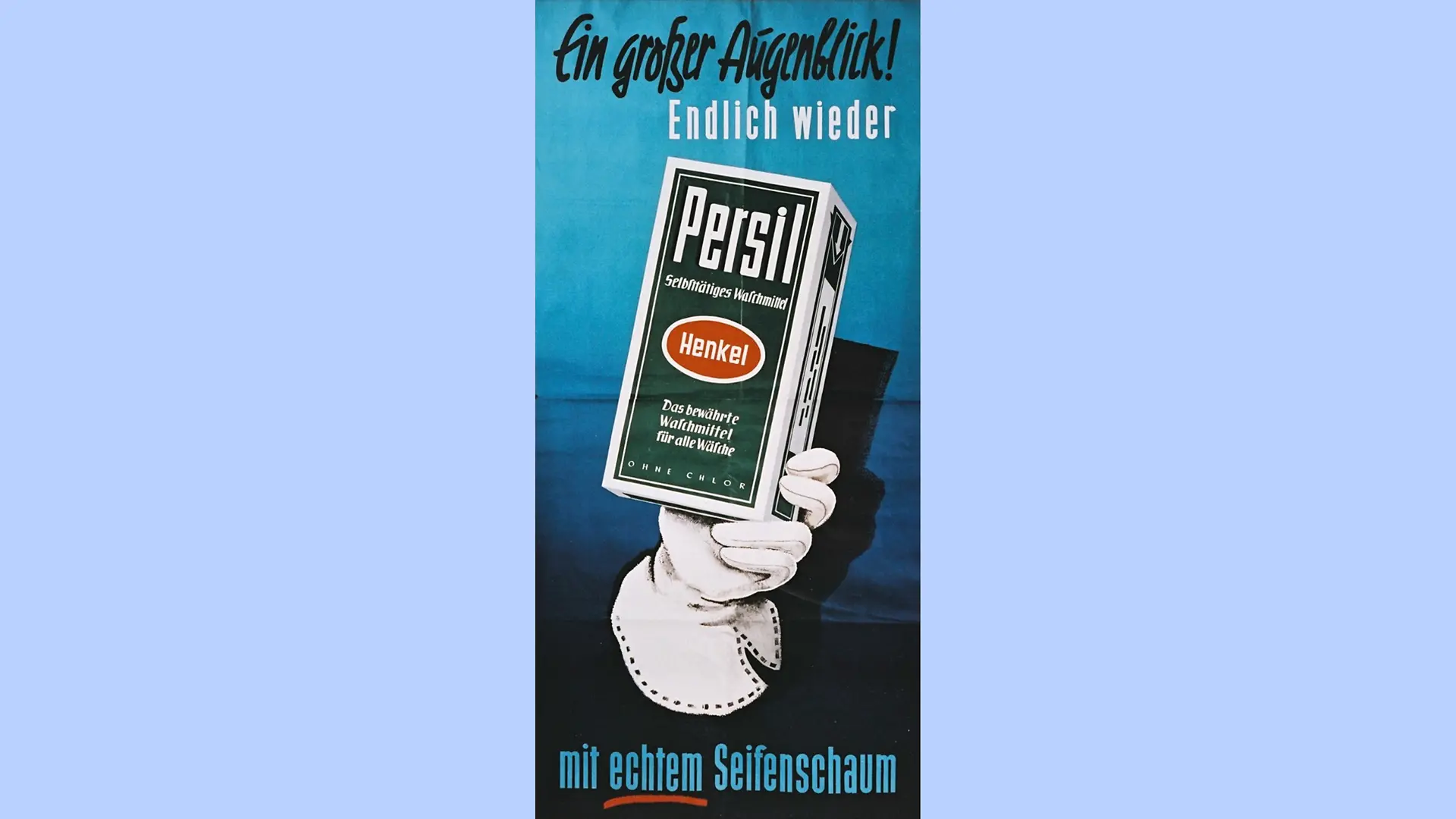

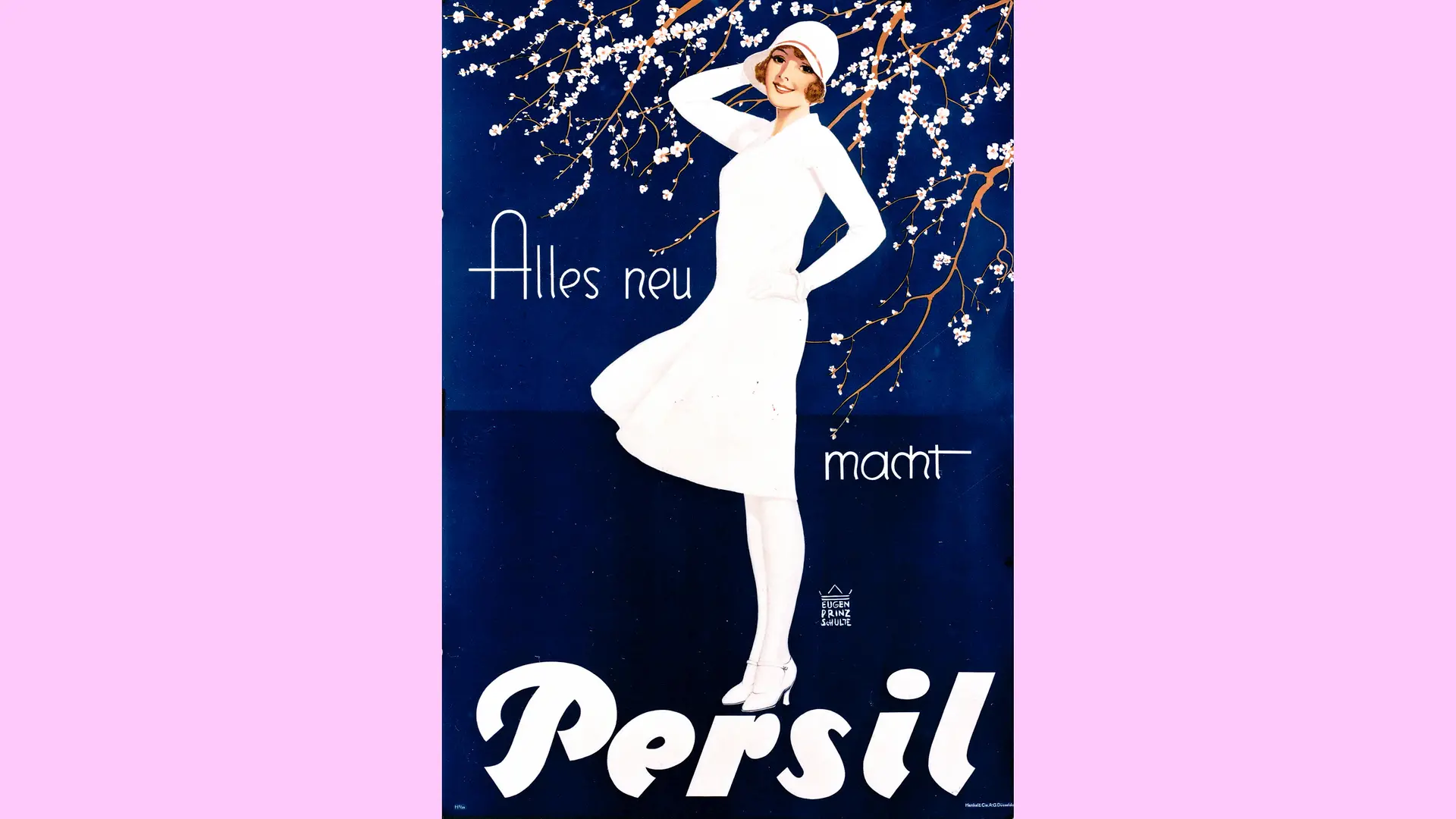

During the Nazi era, Henkel came under pressure from the regime’s autarky efforts to reduce its dependence on imported fats. The so-called “fat gap” – a shortage of domestic fats – hit the company particularly hard, as its detergents relied on vegetable oils and animal fats. As a result, the fat content in the main product Persil had to be significantly reduced as early as 1934 due to government regulations, which affected its quality.

Henkel responded by intensifying research into substitutes. In collaboration with chemist Arthur Imhausen, the Deutsche Fettsäure-Werke GmbH was founded in 1936, producing synthetic fatty acids from coal by-products starting in 1937. By 1940, these became the most important source of substitute fats.

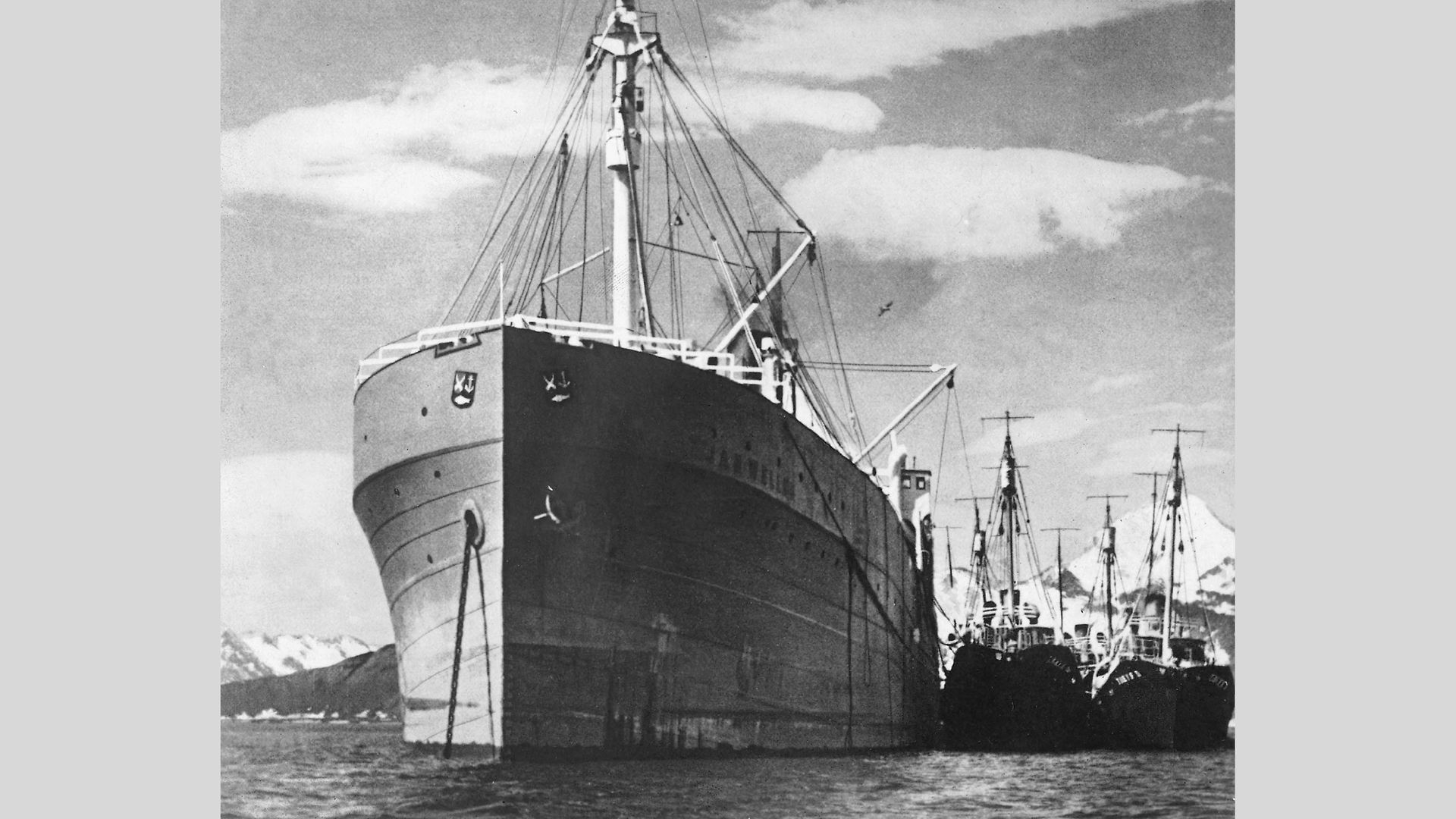

The whaling ship “Jan Wellem” (1936)

In parallel, Henkel pursued another, albeit unusual, source of raw materials: whaling. The Erste Deutsche Walfanggesellschaft (First German Whaling Company) was founded in 1935. Although the three resulting expeditions to Antarctica were technically successful, they were economically unprofitable. Despite propaganda efforts, whaling contributed little to solving the fat problem. The project was discontinued with the outbreak of the Second World War.

Conclusion

The history of Henkel during National Socialism is an example of the widespread gradual adaptation of an originally liberal family business to the dictatorship during this period. Overall, those responsible at Henkel, like many others, acted primarily out of economic calculation and largely ignored the moral responsibility. The picture is mixed when it comes to the workforce: while many workers were merely followers, support for the NSDAP was high among employees and managers. The political development at Henkel is typical of many large German companies at that time: initial distance gave way to pragmatic adaptation and involvement in the Nazi regime.

![A package of Perwoll detergent is positioned in the center of the poster, standing in front of two pieces of clothing. Across the top portion, the text reads: “Die Persilwerke bringen für feine Wäsche und alles Zarte” (“The makers of Persil present [a product] for fine laundry and all delicate items”). At the bottom, the slogan “Zum Säubermachen – Henkelsachen!” (“For cleaning – Henkel products!”) is displayed.](/resource/image/2064484/16x9/1920/1080/4e0394c8703e7756262189d5db160fc3/2165F6B74B62F6D7419B058C1BF5FECB/1949-plakat-perwoll.webp)